Myogenous Orofacial Pain Disorders: A Retrospective Study

Erick Gomez-Marroquin1, Yuka Abe1,2, Mariela Padilla1*, Reyes Enciso3, Glenn T. Clark1

1Orofacial Pain and Oral Medicine, Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry of University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, USA

2Department of Prosthodontics, Showa University School of Dentistry, Tokyo, Japan. Visitor Scholar Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, USA

3Division of Dental Public Health and Pediatric Dentistry, Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry of University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, USA

Abstract

Aim: To assess treatment efficacy in the management of orofacial myogenous conditions by a retrospective study of patients seen at an orofacial pain clinic.

Methods: A single researcher conducted a retrospective review of charts of patients assigned to the same provider, to identify those with myogenous disorders. The reviewed charts belonged to patients of the Orofacial Pain and Oral Medicine Center of the University of Southern California, seeing from June 2018 to October 2019.

Results: A total of 129 charts included a myogenous disorder; the most common primary myogenous disorder was localized myalgia (58 cases, 45.0%). Arthralgia was the most common TMD concomitant condition (82.9%), followed by internal derangement (41.9%). Forty-six patients were given a home-based conservative physical care protocol; ten additional cases also received trigger point injections (lidocaine or mepivacaine) with pain assessed by verbal numerical rating scale (NRS), pre- and post-treatment follow-up within 24 weeks. There was a significant overall pain improvement in NRS pain from pre- to post-treatment (p<0.001), though no difference was found between conservative treatment and trigger points in NRS pain (p=0.130). However, the rate of NRS unit improvement per week in the conservative treatment group was significantly greater than the trigger point group (p=0.036). These apparently contradictory results might be due to the small sample size of the trigger point injections group (n=10).

Conclusion: In this small sample size study, the addition of trigger point injections to conservative treatment provided inconclusive results, further studies are needed.

Introduction

The temporomandibular disorders (TMD) include a group of musculoskeletal and neuromuscular conditions that involve the temporomandibular joints (TMJ), the masticatory muscles, and all associated tissues1,2. In a general population epidemiological study with TMD conditions, a prevalence of 48% presented clinical features of muscle tenderness3.

The etiology of masticatory muscle pain disorders might include overuse of a normally perfused muscle, autonomic changes affecting vascular supply, and even behavioral alterations producing increased contraction4. To identify a tender muscle, digital palpation is usually performed, with a pressure of approximately 1.5 to 1.8 kg5, localizing tenderness or contraction in a muscle band6.

Myogenous chronic pain can be associated with other chronic conditions, such as cervicalgia, lumbalgia and temporomandibular joint pain7. A proposed mechanism for this comorbidity is the convergence of nerve branches from upper cervical region into the spinal trigeminal nucleus8. Other mechanisms for comorbidities in painful conditions include changes at the level of the central nervous system such as the descending modulatory pathways, sleep disorders and psychological issues9. The research diagnostic criteria for TMD (DC/TMD) lists myalgia, myofascial pain, tendonitis, myositis, and spasm as subgroup categories of myogenous TMD pain10, and the International Classification of Orofacial Pain (ICOP) divides the muscle disorders in primary (acute and chronic) and secondary myofascial pain (tendonitis, myositis and muscle spasm)11. Patients with masticatory pain have reported more neck disability and regional muscle sensitivity12.

Myofascial pain is a condition characterized by the presence of trigger points, which are hyperirritable spots, usually within a taut band of skeletal muscle or in the muscle fascia13. For myofascial pain, the treatment protocol includes patient education, muscle stretching exercises, medications, and trigger point injections. There are several patient driven self-help groups for awareness and education, which host web sites and meetings. The extent to which a patient incorporates these self-directed treatments into their life will largely depend on the training they receive and the severity of their problem14. Current evidence supports the use of physical therapy for the treatment of muscular orofacial pain disorders. Stretching exercises have demonstrated to be a cost-effective modality for painful conditions related with temporomandibular disorders15,16. The goal of the exercises is to decrease pain by increasing local blood circulation. One of the exercises frequently used to promote relaxation and to stretch the mandibular elevator muscles involves opening and closing the mouth, with the apex of the tongue positioned on the lingual surface of the maxillary incisors, pronouncing the letter “N” and keeping the tongue in this position. This protocol must be performed several times a day to be effective17,18. The management of myofascial pain also includes the identification and control of risk and perpetuating factors, such as posture, poor sleep, and behavioral issues19.

Regarding pharmacotherapy, the most frequently prescribed medications are analgesics, anti-inflammatories, muscles relaxants and antidepressants20. If a pharmacological approach is selected, the mechanism of action of the drug and side effect profile must be carefully considered in order to maintain patient compliance and tolerability21.

The use of trigger point injections has been described as a suitable treatment modality, although not superior than a more conservative approach such as home-based exercise plan22. The rationale for the use of injections is to produce a mechanical disruption of the trigger point to provide the therapeutic effect. The analgesic effect of a trigger point injection might take more than two weeks to be evident23.

Several indicators might be used to evaluate efficacy of treatment, including improvement of function, reduced pain at palpation, and self-rating scales of pain intensity. The emergency medicine literature reports on plentiful pain scoring systems for assessment of pain. These scoring systems include the 100-mm Visual Analog Scale (VAS), the verbally administered Numeric Rating Scale (NRS), the Color Analog Scale (CAS), and the Verbal Rating Scale (VRS)24. Because of the strong correlation between verbally administered NRS, VAS, and CAS and the close inter-scale agreement, their interchangeable use in the evaluation of adult patients has been suggested25.

The objective of this retrospective study was to assess treatment efficacy for myogenous disorders in the Orofacial Pain and Oral Medicine Center at Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry of USC. The hypothesis was that changes in the pain severity of myogenous disorders was associated with time and that a trigger point injection was effective to relieve myofascial pain.

Materials and Methods

The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines were followed on this study.

Selection Criteria

This is a retrospective study conducted at the Orofacial Pain and Oral Medicine Center of the Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry of University of Southern California. The study followed IRB regulations from University of Southern California (IRB# UP-07-00416), with clinical data collected from charts of patients seen from June 2018 to October 2019. The data was stored in a secure computer with password-protected access. To avoid bias, a single researcher reviewed all the charts of patients assigned to the same provider, to identify those with an International Classification of Diseases (ICD) code corresponding to a myogenous disorder in the assessment section of the chart, and created a de-identified database including demographics, chief complaint, diagnosis, procedure, additional TMD diagnosis, and numerical pain perception by patient’s report. If more than one diagnostic code was reported, up to four were included in the database, labelled as first, second, third or fourth diagnosis. Myalgia in masticatory or cervical muscles, myofascial pain, and trismus/spasm were considered as myogenous disorders and related conditions, identified by the ICD codes (ICD-10 code: M79.11, M79.12, M79.18, and R25.2, respectively). The provider was calibrated for masticatory muscle palpation following the protocol of the Orofacial Pain and Oral Medicine Center of Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry of USC and the DC/TMD criteria, which includes muscle location, one finger palpation to the muscles in resting state, tenderness identification and assessment of referred pain by patient report. The palpation was done by a calibrated provider who was trained to perform palpation with 1.5-2kg.

Treatment

All patients with myogenous pain were treated by the same clinician, and given a home-based conservative physical care protocol, including avoidance of wide mouth opening and hard food, thermal therapy (either moist heat or ice packs), rest position of the jaw and jaw stretches with the tongue positioned in the anterior palate. Trigger point injection was prescribed when active or latent trigger points in the taut bands of masticatory and cervical muscles were identified and patient consented to the treatment. Prescribed medication or oral appliance (stabilization splint) were given if necessary. Other therapeutic modalities, such as peripheral stimulation were not included on this group of patients.

Outcome Assessment

The verbal numerical rating scale (NRS) was used to assess severity of pain on treatment date and follow-up response to therapy (patient education, home protocol, prescription or trigger point injection). The NRS unit was recorded in the appointment for treatment and in the immediate follow-up. If the injection was performed, additional information such as the NRS unit at the time of visit before and after the injection, the number of days between visits, injected muscle site, the type and the volume of anesthetics injected, and the course of treatment was investigated.

Data Analysis

The patients were divided by the principal treatment into injection group and other conservative treatment group. The NRS units of “pre-treatment” at the day of principal treatment and “post-treatment” at the immediate visit within 24 weeks after treatment were analyzed. We calculated the rate of NRS unit improvement due to treatment, which is equivalent of the NRS unit reduction per week. Shapiro-Wilk normality tests were conducted for the NRS units, the number of weeks between the principal treatment and the immediate follow-up, and the rate of improvement. A correlation coefficient between the NRS unit and follow-up period was determined. Then, we applied a Wilcoxon matched-pair signed rank (2 samples) to compare NRS unit of pre-treatment with that of post-treatment in overall cases. In addition, a Mann-Whitney's U test was applied to compare the NRS unit and the improvement rate between groups. Significant level was set at 0.05 (IBM SPSS Statistics version 25).

Results

Sample profile

A total of 167 records of patients with orofacial pain or dysfunction was obtained, of which 129 charts included myogenous disorders as diagnoses. Females were 80.6% of the 129 patients. Patients with pain as a chief complaint were 73.6% (Table 1). The distribution showed 16-25 and 46-55 age groups more prevalent (20.2%) (Table 2).

Table 1: Distribution by chief complaint

|

Chief Complaint |

Female |

Male |

n |

% |

|

Pain |

80 |

15 |

95 |

73.6 |

|

Temporomandibular joint sounds |

12 |

4 |

16 |

12.4 |

|

Limited mandibular range of motion |

7 |

3 |

10 |

7.8 |

|

Other |

5 |

3 |

8 |

6.2 |

|

Total |

104 |

25 |

129 |

|

Table 2: Distribution by age range

|

Age range |

n |

% |

|

Less than 16 |

18 |

14.0 |

|

16-25 |

26 |

20.2 |

|

26-35 |

20 |

15.5 |

|

36-45 |

12 |

9.3 |

|

46-55 |

26 |

20.2 |

|

56-65 |

14 |

10.9 |

|

66 or more |

13 |

10.1 |

When the differential diagnosis is considered, localized myalgia was included in 85.35% of the cases, being the first condition included in the assessment in 45% of the patients. Trismus or spasm was an uncommon diagnosis (3.9% of the cases) (Table 3). Other diagnosis are included in Table 4, and include TMJ arthralgia (82.9%) and internal derangement (41.9%).

Table 3: Distribution by myogenous disorders and related conditions as first, second, third and fourth diagnosis

|

First Diagnosis (n) |

Second Diagnosis (n) |

Third Diagnosis (n) |

Fourth Diagnosis (n) |

|

|

Myalgia (masticatory) |

57 |

36 |

13 |

4 |

|

Myalgia (cervical) |

1 |

29 |

20 |

4 |

|

Myofascial Pain |

13 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

|

Trismus/Spasm |

5 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

Table 4: Myogenous disorders and related conditions

|

ICD-10 |

Identified Diseases |

Myogenous Disorders (n) |

Any Myogenous Disorders |

|||

|

Myalgia (masticatory) |

Myalgia (cervical) |

Myofascial Pain |

Trismus/Spasm |

|||

|

G43.009 |

Migraine without aura |

2 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

|

G44.219 |

Tension type headache, Episodic |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

G44.229 |

Tension type headache, Chronic |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

G47.33 |

Obstructive sleep apnea |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

|

G47.63 |

Sleep related bruxism |

5 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

|

G50.8 |

Trigeminal neuropathy |

6 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

7 |

|

G50.9 |

Trigeminal nerve disorder, unspecified |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

H73.90 |

Tensor Tympani Syndrome |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

K14.6 |

Burning mouth syndrome |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

M06.80 |

Rheumatoid arthritis, TMJ |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

M19.90 |

Osteoarthritis, TMJ |

11 |

5 |

3 |

0 |

14 |

|

M26.62 |

Arthralgia |

94 |

48 |

11 |

5 |

107 |

|

M26.63 |

Articular disc disorder - locking |

6 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

|

M26.69 |

Derangement of TMJ |

46 |

22 |

6 |

1 |

54 |

|

M27.8 |

Condylar hyper/hypoplasia |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

M35.7 |

Joints' Hypermobility |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

M62.48 |

Contracture |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

M67.98 |

Unspecified disorder of synovium and tendon |

0 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

3 |

|

M79.11 |

Myalgia (masticatory) |

53 |

1 |

4 |

56† |

|

|

M79.12 |

Myalgia (cervical) |

53 |

1 |

1 |

53† |

|

|

M79.18 |

Myofascial Pain |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1† |

|

|

R25.2 |

Trismus/Spasm |

4 |

1 |

0 |

4† |

|

†: It represents the number of comorbidities of the listed myogenous disorder and any of the others.

There were no reported adverse side effects in any of the reviewed charts; however, there is no evidence of a specific system for patients to report adverse effects other than the follow up note. Among 129 patients with myogenous disorders, a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) was prescribed to 30 patients (23.3%) as part of the initial treatment, muscle relaxant to 9 patients (7.0%). The overall compliance with follow-up appointment was 53.4%, with 69 patients not showing after treatment. When a trigger point injection was performed, the no-show percentage was 28.6%.

Pain intensity improvement with treatment

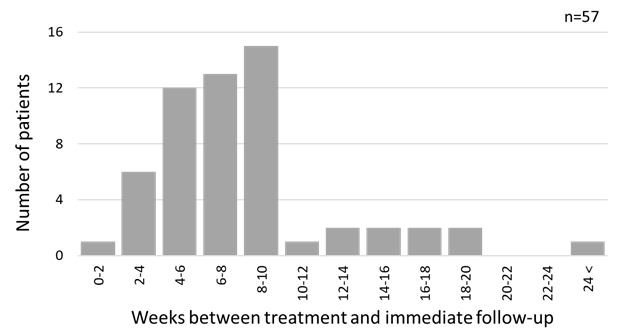

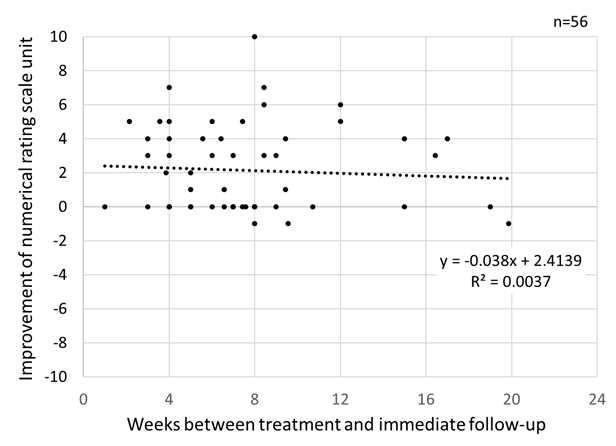

A total of 56 charts of patients with myogenous disorders had NRS pain documentation of both pre-treatment and post-treatment within 24 weeks, including 10 cases where a trigger point injection was performed. As shown in Figure 1, more than 80% of the patients was followed within 10 weeks after the treatment; however, one patient did not show up within 24 weeks. All variables failed the normality test. The median and interquartile range of NRS pain were 7 (range = 3) units for pre-treatment, and 5 (range =5) units for post-treatment, respectively. A Wilcoxon signed rank test revealed a significant pain improvement assessed by NRS, which was a significant decrease in the NRS pain (pre – post), after treatment (p < 0.001). Although the NRS pain improvement after treatment tended to decrease with the follow-up time in weeks, no significant correlation was found between NRS improvement and weeks (Spearman’s rho: -0.092, p=0.502, Kendall’s tau: -0.083, p=0.413) (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Distribution of number of weeks between treatment and immediate follow-up

Figure 2: Improvement in numerical rating scale unit for pain after treatment

Trigger point injections

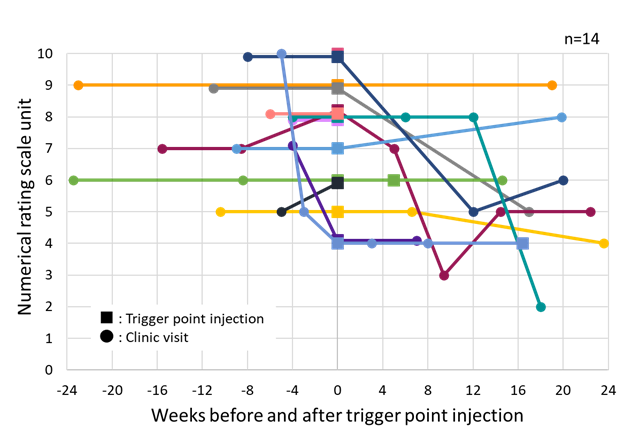

The trigger point injection was performed by the same calibrated clinical provider in 14 cases. Four of the patients did not show up after the injection treatment. Although most of the patients reported significant relief of pain immediately after the injection, only 3 cases improved the NRS unit at the time of follow-up, furthermore, 7 cases stayed about the same (Figure 3). Prior to the injection, 11 patients complained that there was no obvious change in the pain severity (±1 NRS unit) since the preceding visit. The most frequent location of injection was the unilateral masseter muscle (10 cases, 71.4%), followed by the bilateral masseter muscle (2 cases), and the ipsilateral side of masseter and temporalis muscles (2 cases). The injection was performed using anesthetics of 1% or 2% lidocaine (12 cases), or 3% mepivacaine (2 cases), and a post-procedure stretching exercise protocol was indicated to the patient. The amount of anesthetic ranged between 0.5 to 1.0 mL per injected site. No injection was prescribed at the first visit, and 11 patients received the injection at the second visit (78.6%). Second trigger point injection was prescribed for 4 patients within 5-46 weeks due to continuous complaint, but no patient received three or more injections in the reviewed records.

Each plot represents each patient who received trigger point injection in masticatory muscles. All patients received trigger point injection at the time of “0.” One of the patients is not shown in this figure because of no visit within 24 weeks. Four of the patients did not show up after the injection treatment.

Figure 3: Change in numerical rating scale unit for pain before and after trigger point injection within 6 months

Comparison of pain intensity improvement between trigger point injections and conservative treatment

There was no significant difference in the NRS pain improvement per week (pre – post) between the conservative treatment group and trigger point injection group (Mann-Whitney’s U test, p = 0.130) though the median NRS pain improved 2.5 units in the conservative treatment group (interquartile range = 4.00) compared to 0 units in the injection group (interquartile range = 0.75). However, the rate of NRS unit improvement per week in the conservative treatment group was significantly greater than that in the injection group (Mann-Whitney’s U test, p = 0.036). The median rate of NRS unit improvement per week was -0.3 units in the conservative treatment group (interquartile range = 0.72) and 0 units in the injection group (interquartile range = 0.15). These apparently contradictory results might be due to the small sample size of the trigger point injections group (n=10).

Discussion

The data on this research showed that the most common myogenous disorder in the studied population was localized myalgia in the masticatory muscle, and that the response to a trigger point injection is not superior to a home-based conservative physical care protocol. The main limitations of the study were the limited number of cases, high non-show ratio, the difficulty to measure compliance with home-based therapy, and the lack of a standardized system to report adverse effects of the intervention. Masseter muscle pain has been frequently reported in patients with TMD26, and it might lead to a reorganization of the functional capabilities of mastication involving anterior temporalis as well27. Proposed mechanisms for myalgia include inflammation, tonic disorders28, and maladaptive behaviors29. Both masseter and temporalis muscles are closing muscles, involved in mastication and jaw movements, and have been related with TMD complains30. The most common associated conditions in the present study were arthralgia and internal derangement, all part of the TMD umbrella which includes pain in TMJ and masticatory muscles, articular noises, earache, headache, and limited jaw function. Cervical pain was not frequent as a primary disorder, and there are mixed results in published studies. Weber et al. (2012), studying a group of 71 women (19-35 years), concluded that the presence of TMD resulted in higher frequency of cervical pain31; however, Ries et al. (2014) failed to prove that relationship32. When the electromyographic activity of masticatory and cervical muscles was analyzed, there was evidence of muscle interactions of both groups, with an increased contraction of splenius capitis and upper trapezius during resisted jaw opening33. Our results indicated a close relationship between myalgia in masticatory muscle and that in cervical muscle among the myogenous disorders.

In cross-sectional and case-control studies, frequency of TMD was consistently greater in females than in males. Gender and sex distinction in pain sensitivity and analgesia have been explained by genetic, neurophysiologic, and psychosocial differences, with reports of women perceiving more pain34,35. Queme and Jankowski (2019) suggested that the gender differences are related with the mechanism of muscle pain in immune signaling, circuit activation, and higher order brain structures36. Sorge and Totsch (2017) also indicated the role of biological differences in the immune system as an explanation for the female predominance in chronic pain states37.

In adults, age-specific prevalence displays a higher incidence among people in their 40s, and lower in both younger and older age groups38. The demographics in our study were similar to the reported data, with more females affected and patients over 46 years of age; however, we did find that the group from 16 to 25 years of age presented myogenous disorders as well. Loster et al. (2017) reported that the prevalence of muscle disorders in a high school population (average 17.89 years old) was 13.1%39, and Christidies et al. (2019) reported that TMD in children and adolescents was a common occurrence40.

Regarding trigger point injection, our results indicated that trigger point injections with anesthetic could not always provide favorable response to pain reduction but could bring immediate pain relief. Similar results were shown by Roldan et al. (2020) that the mean NRS scores of 7.44 before injection of lidocaine combined with steroid was decreased to 1.76 immediately after injection but it resulted in 4.14 at 2-week follow-up41. In comparison between trigger point injection and conservative treatment, a randomized controlled trial by Lugo et al. (2016) reported that there were no differences between combined treatment of lidocaine injection and conservative physical therapy and the individual treatments42.

Trigger point injection is not necessarily performed to patients with myofascial pain, but we intended to relieve persistent muscle soreness and tightness by mechanical disruption of trigger point needling1. Our study patients who received trigger point injection were limited in number and suffering prolonged pain, that is probably why the rate of NRS unit improvement in the injection group was not as good as that in the conservative treatment group. The efficacy of conservative therapy, including counseling and exercises, has been widely reported as a successful approach43. Moist heat applications, for example, have shown to produce relief of pain and decrease muscle tension44. In a study with 40 patients with muscle tenderness to palpation, reassurance and education regarding jaw posture and relaxation of masticatory muscles, combined with physical therapy provided pain reduction and function improvement45.

Although the response to conservative treatment has been reported as successful for pain reduction and improvement on function46, one of the main limitations of the study is the substantial number of patients failed to show up to follow-up visits, either after initial consultation or posterior to a trigger point injection, situation which could compromise the prognosis of their condition. Published data on attendance to scheduled appointments shows that nonattendance is a frequent problem affecting the ambulatory medicine system47. It has been shown that a reminder system that includes automatic phone calls or text messages can increase patient attendance. An intervention focused on specific patient characteristics has been suggested to further increase the success rate of appointment reminders system48; however, the non-attendance could be related with improvement of the condition. Alpert (2014) indicated that the most important factor for improving therapeutic adherence is patient’s understanding and education, and the developing of a trusting relationship between provider and patient49.

Regarding response to treatment of orofacial myogenous disorders, it is important to consider the possibility of a natural regression of the disease, and the difficulty to conclude that the provided relief is solely the result of an intervention. The placebo effect and the changes on patient’s situation are not considered on this discussion. The present study is applicable to the selected population, and more research is required to establish generalization of the findings.

Conclusions

In this small sample study, the addition of trigger point injections to conservative treatment provided inconclusive results, further studies are needed. The results of this study stress the importance to consider conservative treatment when dealing with orofacial myogenous disorders. More research is needed to clarify the role of any intervention, as well as to understand the high rate of non-attendance to follow up appointments.

List of Abbreviations

TMD Temporomandibular disorders; TMJ Temporomandibular joint; NRS Numerical rating scale; DC/TMD Diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders; ICOP International classification of orofacial pain; VAS Visual analog scale; CAS Color analog scale; VRS Verbal rating scale; USC University of Southern California; STROBE Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology; ICD International classification of diseases; NSAID non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Conflict of Interest

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Authors’ Contributions

Dr. Erick Gomez –Marroquin: Clinician who treat all patients included in the study.

Dr. Yuka Abe: Created the de-identified database and classified the charts accordingly with the diagnosis.

Dr. Mariela Padilla: Analyzed the data and created the key points for the discussion.

Dr. Reyes Enciso: Performed the statistical analysis.

Dr. Glenn Clark: Advisory role in the interpretation of the results.

References

- De Leeuw R, Klasser G. Orofacial Painâ¯: Guidelines for Assessment, Diagnosis, and Management. Fifth edition. Chicago: Quintessence Publishing Co, Inc; 2013.

- Gauer R, Semidey M, Gauer R. Diagnosis and treatment of temporomandibular disorders. American family physician. 2015; 91(6): 378-386.

- LeResche L. Epidemiology of temporomandibular disorders: implications for the investigation of etiologic factors. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1997; 8(3): 291-305.

- Nijs J, Daenen L, Cras P, et al. Nociception affects motor output: a review on sensory-motor interaction with focus on clinical implications. Clin J Pain. 2012; 28(2): 175-181.

- Fernandes G, Gonçalves DAG, Conti P. Musculoskeletal Disorders. Dent Clin North Am. 2018; 62(4): 553-564.

- Gerwin RD. Diagnosis of myofascial pain syndrome. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2014; 25(2): 341-355.

- Plesh O, Adams SH, Gansky SA. Temporomandibular joint and muscle disorder-type pain and comorbid pains in a national US sample. J Orofac Pain. 2011; 25: 190-198.

- Raphael KG, Marbach JJ, Gallagher RM. Somatosensory amplification and affective inhibition are elevated in myofascial face pain. Pain Med. 2000; 1: 247-253.

- Cohen SP, Mao J. Neuropathic pain: mechanisms and their clinical implications. BMJ. 2014 Feb 5; 348: f7656.

- Schiffman E, Ohrbach R, Truelove E, et al. Diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders (DC/TMD) for clinical and research applications: Recommendations of the international RDC/TMD consortium network* and orofacial pain special interest group†. J Oral Facial Pain Headache. 2014; 28: 6–27.

- International Classification of Orofacial Pain, 1st edition (ICOP). Cephalalgia. 2020; 40(2): 129-221.

- da Costa DR, de Lima Ferreira AP, Pereira TA, et al. Neck disability is associated with masticatory myofascial pain and regional muscle sensitivity. Arch Oral Biol. 2015; 60(5): 745-752.

- Fricton J. Myofascial pain: mechanisms to management. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2016; 28(3): 289-311.

- Clark GT. Classification, causation and treatment of masticatory myogenous pain and dysfunction. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2008; 20(2): 145-157.

- de Freitas RF, Ferreira MA, Barbosa GA, et al. Counselling and self-management therapies for temporomandibular disorders: a systematic review. J Oral Rehabil. 2013; 40(11): 864-874.

- Manfredini D. A better definition of counselling strategies is needed to define effectiveness in temporomandibular disorders management. Evid Based Dent. 2013; 14(4): 118-119.

- Moraes ADR, Sanches ML, Ribeiro EC, et al. Therapeutic exercises for the control of temporomandibular disorders. Dental Press J Orthod. 2013; 18(5): 134-139.

- Michelotti A, Steenks MH, Farella M, et al. The additional value of a home physical therapy regimen versus patient education only for the treatment of myofascial pain of the jaw muscles: short-term results of a randomized clinical trial. J Orofac Pain. 2004; 18(2): 114-125.

- Jaeger B. Myofascial trigger point pain. Alpha Omegan. 2013; 106(1-2): 14-22.

- Borg-Stein J, Iaccarino M. Myofascial pain syndrome treatments. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2014; 25(2): 357-374.

- Borg-Stein J, Iaccarino MA. Myofascial pain syndrome treatments. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2014; 25(2): 357-374.

- Aksu Ö, Pekin DoÄan Y, Sayıner ÇaÄlar N, et al. Comparison of the efficacy of dry needling and trigger point injections with exercise in temporomandibular myofascial pain treatment. Turk J Phys Med Rehabil. 2019; 65(3): 228-235.

- Nouged E, Dajani J, Ku B, et al. Local anesthetic injections for the short-term treatment of head and neck myofascial pain syndrome: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Oral Facial Pain Headache. 2019; 33(2): 183–198.

- Castarlenas E, de la Vega R, Jensen M, et al. Self-report measures of hand pain Intensity: current evidence and recommendations. Hand clinics. 2016; 32(1): 11-19.

- Hjermstad MJ, Fayers PM, Haugen DF, et al. European Palliative Care Research Collaborative (EPCRC). Studies comparing Numerical Rating Scales, Verbal Rating Scales, and Visual Analogue Scales for assessment of pain intensity in adults: a systematic literature review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011 Jun;41(6):1073-93. Simons DG. Neurophysiologic basis of pain caused by trigger points, APS Journal. 1994; 3: 17-19.

- Ferreira PM, Sandoval I, Whittle T, et al. Reorganization of masseter and temporalis muscle single motor unit activity during experimental masseter muscle pain. J Oral Facial Pain Headache. 2020; 34(1): 40–52.

- Glaubitz S, Schmidt K, Zschüntzsch J, et al. Myalgia in myositis and myopathies. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2019; 33(3): 101433.

- Ohrbach R, Michelotti A. The role of stress in the etiology of oral parafunction and myofascial pain. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2018; 30(3): 369-379.

- Pedroni CR, de Oliveira AS, Bérzin F. Pain characteristics of temporomandibular disorder: a pilot study in patients with cervical spine dysfunction. J Appl Oral Sci. 2006; 14(5): 388-392.

- Ferreira MC, Porto de Toledo I, Dutra KL, et al. Association between chewing dysfunctions and temporomandibular disorders: a systematic review. J Oral Rehabil. 2018; 45(10): 819-835.

- Weber P, Corrêa EC, Ferreira Fdos S, et al. Cervical spine dysfunction signs and symptoms in individuals with temporomandibular disorder. J Soc Bras Fonoaudiol. 2012; 24(2): 134-139.

- Ries LGK, Graciosa MD, Medeiros DLD, et al. Influence of craniomandibular and cervical pain on the activity of masticatory muscles in individuals with temporomandibular disorder. Codas. 2014; 26(5): 389-394.

- Armijo-Olivo S, Magee DJ. Electromyographic activity of the masticatory and cervical muscles during resisted jaw opening movement. J Oral Rehabil. 2007; 34(3): 184-194.

- Shinal RM, Fillingim RB. Overview of orofacial pain: epidemiology and gender differences in orofacial pain. Dent Clin North Am. 2007; 51(1): 1-18.

- Pieretti S, Di Giannuario A, Di Giovannandrea R, et al. Gender differences in pain and its relief. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2016; 52(2): 184-189.

- Queme LF, Jankowski MP. Sex differences and mechanisms of muscle pain. Curr Opin Physiol. 2019; 11: 1-6.

- Sorge RE, Totsch SK. Sex differences in pain. J Neurosci Res. 2017; 95(6): 1271-1281.

- Maixner W, Diatchenko L, Dubner R, et al. Orofacial pain prospective evaluation and risk assessment study – the OPPERA study. J Pain. 2011; 12(11): T4-T11.e1-2.

- Loster JE, Osiewicz MA, Groch M, et al. The prevalence of TMD in polish young adults. J Prosthodont. 2017; 26(4): 284-288.

- Christidis N, Lindström N, danshau E, et al. Prevalence and treatment strategies regarding temporomandibular disorders in children and adolescents- a systematic review. J Oral Rehabil. 2019; 46(3): 291-301.

- Roldan CJ, Osuagwu U, Cardenas-Turanzas M, et al. Normal saline trigger point injections vs conventional active drug mx for myofascial pain syndromes. Am J Emerg Med. 2020; 38(2): 311-316.

- Lugo LH, García HI, Rogers HL, et al. Treatment of myofascial pain syndrome with lidocaine injection and physical therapy, alone or in combination: a single blind, randomized, controlled clinical trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016; 17: 101.

- Wieckiewicz M, Boening K, Wiland P, et al. Reported concepts for the treatment modalities and pain management of temporomandibular disorders. J Headache Pain. 2015; 16: 106.

- Furlan RM, Giovanardi RS, Britto AT, et al. The use of superficial heat for treatment of temporomandibular disorders: an integrative review. Codas. 2015; 27(2): 207-212.

- De Laat A, Stappaerts K, Papy S. Counseling and physical therapy as treatment for myofascial pain of the masticatory system. J Orofac Pain. 2003; 17(1): 42-49.

- Dworkin SF, Huggins KH, Wilson L, et al. A randomized clinical trial using research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders-axis II to target clinic cases for a tailored self-care TMD treatment program. J Orofac Pain. 2002; 16(1): 48-63.

- Giunta DH, Alonso Serena M. Nonattendance rates of scheduled outpatient appointments in a university general hospital. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2019; 34(4): 1377-1385.

- Junod Perron N, Dominicé Dao M, Kossovsky M, et al. Reduction of missed appointments at an urban primary care clinic: a randomised controlled study. BMC Fam Pract. 2010; 11: 79.

- Alpert JS. Compliance/adherence to physician-advised diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. Am J Med. 2014; 127(8): 685-686.