Mini Review of An Opioid-Sparing Protocol for the Management of Patients Undergoing Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy

Jay Suggs*, Garrett G. Perry

Crestwood Medical Center, One Hospital Drive, Huntsville, AL, USA

Introduction

Opioids are frequently overprescribed by surgical specialties1-4. Nearly half of patients who did not take opioids their last surgical hospitalization day are still given a prescription for opioid pain medicines upon discharge4. Additionally, the addictive nature of opioid usage can be seen in the bariatric population with one study reporting 5.8% of opioid-naïve patients continuing to use opioids 6 months after bariatric surgery and 14.2% at 7 years5. A legitimate postoperative opioid prescription can act as a gateway to chronic, even illegitimate, narcotic use.

To combat the opioid epidemic as well as improve outcomes, multimodal analgesics protocols (e.g., ERAS protocols) have been adopted by many surgical specialties. These protocols have the advantage of addressing multiple pain pathways without causing opioid-related adverse effects (nausea, vomiting, ileus, respiratory depression, and altered mental status) which cause delayed patient recovery6-8. Of particular importance to bariatric patients are uncontrolled nausea resulting in poor oral intake which results in a delay of discharge9 and full recovery.

We hypothesized that postoperative pain could be adequately managed and that patients would have a quicker return to baseline with an opioid-sparing protocol. The goal was to determine if an opioid-sparing protocol could safely and effectively decrease opioid use during the postoperative period.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study was conducted for adult patients between the ages of 18 and 70 years old undergoing a laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) by a single surgeon at a single institution. Each arm of the cohort was made of 200 patients. Standard, accepted criteria for bariatric surgery included that of a body mass index (BMI) of 40 or greater, or a BMI of 35–39 with obesity related comorbidities. Patients that were chronically taking opioids prior to surgery were not excluded from the study.

Pain scores and recovery time (measured as return to baseline activity) were the primary outcomes and were collected within one year via phone surveys, although participation was relatively low. Both inpatient postoperative and at home pain score surveys were conducted utilizing a 0-10 scale with 0 representing no pain and 10 representing the worst pain experience in the person’s life. There were also a number of secondary outcomes analyzed. A summary of both primary and secondary outcomes are listed in Table 1. The protocols for both the control group and opioid-sparing groups can be viewed in Table 2.

Table 1: Measured Outcomes

|

|

Control (n = 200) |

Opioid-sparing (n = 200) |

P value |

|

Total MME during admission, mean (SD) |

34.5 (24.7) |

30.7 (25.8) |

.04 |

|

Intraoperative, mean (SD) |

53.0 (18.1) |

51.6 (19.2) |

.46 |

|

Postoperative (in hospital), mean (SD) |

16.1 (14.5) |

10.4 (11.0) |

< .001 |

|

Rescue antiemetic given, n (%) |

49 (24.5%) |

62 (31.0%) |

.18 |

|

LOS, d, mean (SD) |

1.1 (0.32) |

1.1 (0.32) |

.79 |

|

30-d readmission, n (%) |

10 (5.0%) |

5 (2.5%) |

.29 |

|

SSI, n (%) |

1 (0.5%) |

1 (0.5%) |

>.99 |

|

Blood transfusion, n (%) |

1 (0.5%) |

1 (0.5%) |

>.99 |

MME = morphine milligram equivalents; SD = standard deviation; LOS = length of stay; SSI = surgical site infection

Table 2: Opioid-sparing protocol compared with historic controls

|

Opioid-sparing protocol |

Historic control |

|

|

Preoperative |

Celecoxib 400 mg PO Gabapentin 300 mg PO |

None |

|

Intraoperative |

Inhalation anesthetics, propofol, and multimodal analgesia Plus TAP block with 0.5% bupivicaine with epinephrine |

Inhalation anesthetics, propofol, and multimodal analgesia |

|

Postoperative in hospital |

Ketorolac 30 mg IV every 6 hours Acetaminophen 1000 mg IV or PO every 6 hours Morphine IV or morphine equivalent for breakthrough pain |

Ketorolac 30 mg IV every 6 hours Acetaminophen 1000 mg IV or PO every 6 hours Morphine IV or MME for breakthrough pain |

|

Postoperative at home |

Gabapentin 300 mg PO twice daily Celecoxib 200 mg PO twice daily Acetaminophen 1000 mg PO every 6 hours as needed Tramadol for breakthrough pain |

Hydrocodone-Acetaminophen 2.5-167 mg per 5 ml, 15-30 ml PO every 4-6 hours as needed (Dispense: 400 ml) |

TAP = transversus abdominis plane; MME = morphine milligram equivalent

Unpaired t-tests were used to compare means of continuous variables. Categorical and dichotomous variables were expressed as percentages and compared using Fisher’s exact tests. For all analyses, a 2-sided α level of .05 was taken as a reference to detect statistical significance.

Results

The study included 400 patients (200 in each arm). 165 patients participated in the phone survey, with 80 from the control group and 85 from the opioid-sparing group. Of note the control group had a significantly higher mean BMI (47.7 versus 45.6 kg/m2, p .01) and body weight (134 versus 128 kg, p = .03). Otherwise, the baseline characteristics of each group were identical. The average recovery time was significantly shorter in the opioid-sparing group (18.9 versus 35.3 days, p = 0.043). There was no significant difference in mean postoperative pain scores. The opioid-sparing group required significantly fewer opioids postoperatively (10.4 versus 16.1 MME, p < 0.001). Only 1 out of 200 patients requested an opioid prescription after discharge.

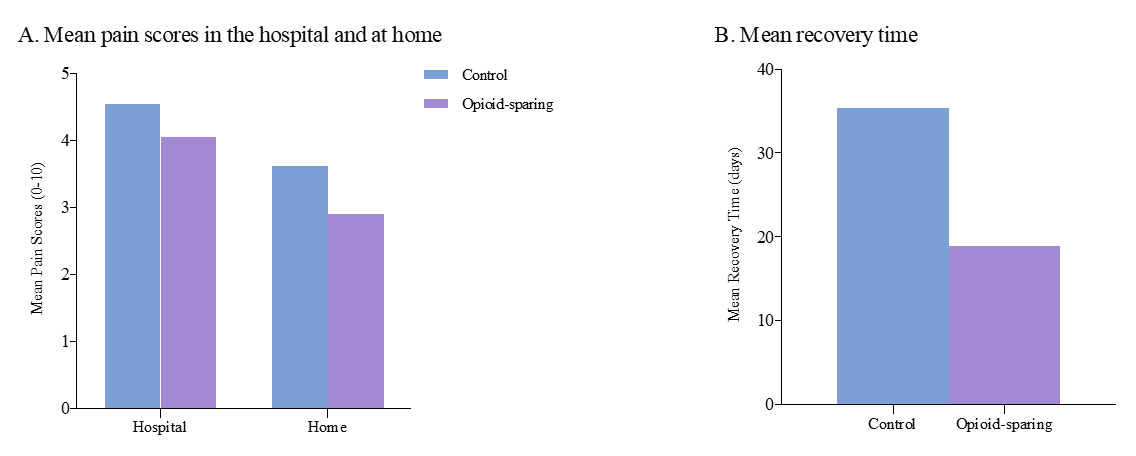

There was no significant difference in mean pain scores between the control and opioid sparing group in the hospital (4.0 versus 4.5, p = .28) or at home (2.9 versus 3.6, p = .08) seen in Figure 1a. Additionally, the average recovery time was significantly shorter in the opioid sparing group (18.9 versus 35.3 d, p = .04) seen in Figure 1b. Of the secondary outcomes measured only the mean total MME during admission and postoperative (in hospital) were statistically significant seen in Table 1.

Figure 1a: Mean pain scores in the hospital and at home before and after implementation of opioid-sparing protocol. Pain score was rated from 0 to 10, where 0 represents no pain and 10 represents the worst possible pain. Figure 1b: Mean recovery time before and after protocol implementation. Recovery time is the length of time (days) it took for the patient to return to baseline activity level.

Discussion

Our study showed that postoperative pain after LSG can be effectively controlled with limited opioid use in the hospital and essentially no opioids after discharge. Additionally, the opioid sparing group recovered faster with only a single patient requiring an opioid prescription. The result of this study is consistent with prior inpatient studies on the bariatric population showing multimodal analgesics as effective, decreases perioperative opioid use, and reduces opioid-related adverse events9,12-18. Of note, 20% of the control arm took no opioids after discharge and of the remaining 80%, only 10% took half or more. The protocol that was developed for the opioid-sparing arm was developed based on review of literature and then modified based on availability at our institution.

There were some limitations to this study. Data was collected retrospectively, and therefore cannot be used to draw strong conclusions about causation. The phone survey results were subject to recall bias due to the amount of time that had passed since their LSG. There was also limited participation in the follow-up survey with only 41% of the patients included in the study. Compliance with protocol medications and variability with anesthesia providers are also potential limitations.

Conclusion

The study supports the hypothesis that the implementation of an opioid-sparing pain regimen can provide effective pain control throughout the entire postoperative period and shorten the recovery time among patients having undergone a LSG.

Since this study was conducted, several changes to the protocol have been made. The current inpatient protocol can be viewed in Table 3 and outpatient protocol can be viewed in Table 4. Tramadol, for breakthrough pain, is no longer used; additionally, IV acetaminophen has been switched to the equivalent oral dose. A higher volume of bupivacaine in the transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block is utilized, and surgeons have become more adept at administering it in the correct plane. The addition of IV ketamine intraoperatively, as well as further reductions in intraoperative narcotic use, have been made.

Table 3: Dr. Suggs’ Inpatient Laparoscopic Abdominal Surgery Pain and Nausea Management Protocol

|

Pre-Op Morning of Surgery (with small sip of water) |

Intra-Op |

Post-Op (inpatient) |

|

Celecoxib 200mg 2 capsules PO |

Ketorolac 30mg IV |

Ketorolac 30mg IV Q6H |

|

Gabapentin 300mg PO |

Zofran 4mg IV |

Decadron 10mg IV 8 hours after intra-op dose |

|

Acetaminophen 1000mg PO (in preop holding) |

Decadron 10mg IV |

Acetaminophen 1000mg PO Q6H |

|

Scopolamine patch post-auricular on arrival |

Ketamine 25mg IV |

Morphine (or other) IV narcotic PRN pain |

|

Aprepitant (Emend) 40 or 80mg PO |

TAP Block – 30mL 0.5% Bupivacaine at incision requiring fascial closure incision |

Aprepitant (Emend) 40 or 80mg PO |

Table 4: Dr. Suggs’ Outpatient Laparoscopic Abdominal Surgery Pain and Management Protocol

|

Week 1 |

Gabapentin 300mg PO BID Celecoxib 200mg PO BID Acetaminophen 1000mg PO Q6H PRN pain |

|

Week 2 |

Gabapentin 300mg PO daily Celecoxib 200mg PO daily Acetaminophen 1000mg PO Q6H PRN pain |

|

Week 3 |

Celecoxib 200mg PO daily PRN pain or Ibuprofen 400mg PO Q6H PRN pain Acetaminophen 1000mg PO Q6H PRN pain |

|

Week 4 |

Acetaminophen 1000mg PO Q6H PRN pain |

We continue to have great outcomes, including rapid return to work, great pain and nausea control, low readmission, and low ER visit rates. In fact, less than 1 in 400 patients require an opioid prescription. Perhaps most significantly, select lower risk patients are now able to have a LSG as an outpatient, usually being discharged home within 4 hours of arriving in the same day surgery unit. This, of course, has required further refinement in the opioid-sparing protocol as well as a specialized outpatient surgery protocol.

If you asked “what is the most important part of your protocol for reducing opioid use, great pain control, and improving back to work time?” I would say: A great TAP block; then IV ketorolac and nausea reduction with a variety of meds; and maximizing use of acetaminophen and celecoxib. We may possibly transition to performing an ultrasound-guided true TAP block on both sides of the abdomen preoperatively, as in the literature as well as anecdotally in my colleagues’ experience it can result in completely numb the entire abdomen for over 24 hours. Many patients discontinue taking celecoxib and gabapentin early, making me question their importance postoperatively. Also, some patients cannot take one or both of these drugs as part of the pre-op protocol. And, many don’t need acetaminophen for very long either. Treatment of post-operative pain and reduction of opioid use in surgical patients is rapidly evolving, so stay tuned! For further information or additional details about the original study that this mini review was based upon please see the full article entitled “An Opioid-Sparing Protocol Improves Recovery Time and Reduces Opioid Use After Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy” that can be found in the journal Obesity Surgery19.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2018 Annual Surveillance Report of Drug-Related Risks and Outcomes — United States. Surveillance Special Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Published August 31, 2018. Accessed February 5, 2020 from https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/pubs/2018-cdc-drug-surveillance-report.pdf.

- Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, et al. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths - United States, 2013-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018; 67(5152): 1419-1427.

- Cicero TJ, Ellis MS, Surratt HL, et al. The changing face of heroin use in the United States: a retrospective analysis of the past 50 years. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014; 71(7): 821-826.

- Hall MJ, Schwartzman A, Zhang J, et al. Ambulatory surgery data from hospitals and ambulatory surgery centers: United States, 2010. Natl Health Stat Report. 2017; (102): 1-15.

- Brethauer SA, Grieco A, Fraker T, et al. Employing Enhanced Recovery Goals in Bariatric Surgery (ENERGY): a national quality improvement project using the Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2019; 15(11): 1977-1989.

- Brummett CM, Waljee JF, Goesling J, et al. New persistent opioid use after minor and major surgical procedures in US adults. JAMA Surg. 2017; 152(6): e170504.

- Hill MV, McMahon ML, Stucke RS, et al. Wide Variation and Excessive Dosage of Opioid Prescriptions for Common General Surgical Procedures. Ann Surg. 2017; 265(4): 709-714.

- Bicket MC, Long JJ, Pronovost PJ, et al. Prescription opioid analgesics commonly unused after surgery: a systematic review.JAMA Surg. 2017; 152(11): 1066-1071.

- Friedman DT, Ghiassi S, Hubbard MO, et al. Postoperative opioid prescribing practices and evidence-based guidelines in bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2019; 29(7): 2030-2036.

- Chen EY, Marcantonio A, Tornetta P 3rd. Correlation between 24-hour predischarge opioid use and amount of opioids prescribed at hospital discharge.JAMA Surg. 2018; 153(2): 174859.

- Ahmed OS, Rogers AC, Bolger JC, et al. Meta-Analysis of Enhanced Recovery Protocols in Bariatric Surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2018; 22(6): 964-972.

- Thorell A, MacCormick AD, Awad S, et al. Guidelines for perioperative care in bariatric surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society recommendations. World J Surg. 2016; 40(9): 2065-2083.

- Ng JJ, Leong WQ, Tan CS, et al. A multimodal analgesic protocol reduces opioid-related adverse events and improves patient outcomes in laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2017; 27(12): 3075-3081.

- Smith ME, Lee JS, Bonham A, et al. Effect of new persistent opioid use on physiologic and psychologic outcomes following bariatric surgery. Surg Endosc. 2019; 33(8): 2649-2656.

- King WC, Chen JY, Belle SH, et al. Use of prescribed opioids before and after bariatric surgery: prospective evidence from a U.S. multicenter cohort study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017; 13(8): 1337-1346.

- Horsley RD, Vogels ED, McField DAP, et al. Multimodal postoperative pain control is effective and reduces opioid use after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2019; 29(2): 394-400.

- Saurabh S, Smith JK, Pedersen M, et al. Scheduled intravenous acetaminophen reduces postoperative narcotic analgesic demand and requirement after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015; 11(2): 424-430.

- Song K, Melroy MJ, Whipple OC. Optimizing multimodal analgesia with intravenous acetaminophen and opioids in postoperative bariatric patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2014; 34(Suppl 1): 14S-21S.

- Pardue B, Thomas A, Buckley J, et al. An opioid-sparing protocol improves recovery time and reduces opioid use after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2020; 30(12): 4919-4925.